Roger Federer

More than a year after his retirement, Roger Federer remains the poster boy for the one-handed backhand – tennis’s most aesthetic shot. Yet he could also be the key to its decline.

When the ATP rankings were updated on Monday, there was no single-hander in the world’s top 10 for the first time since the chart’s inauguration, all the way back in 1973.

The shift represents a victory for the modern style of power baseline tennis as opposed to all-court mastery or net-play. Some of the causes are systemic, such as changing racket technology. Others are more personal, like Federer’s struggles at the (two) hands of Rafael Nadal.

“You go back to that period around 2003 and 2004 and Roger was so dominant,” says the British coach Calvin Betton. “But then Rafa came along and started hitting big, high-bouncing balls into the Federer backhand. When Rafa got on top in their rivalry, it created a stigma for the single-hander.”

Admittedly, Federer made a late-career upgrade to his backhand, winning six of his last seven meetings with Nadal to swing the overall balance back a little. (The scorecard finished at 24-16 in Nadal’s favour.)

But the damage was already done. The image of Federer flailing away at shoulder-level backhands, particularly on the high-bouncing clay of Roland Garros, had sunk deep into the sporting consciousness.

Nadal’s dominance over Federer lasted more than a decade – from 2005 to 2016 – and personified a wider stylistic change within the game. This was the period when natural gut strings were being phased out by polyester. Here was tennis’s answer to the Roland synthesiser, which forced traditional pianos out of recording studios over the course of the 1980s.

Polyester strings last longer, impart more spin, and give you greater power. On the downside, though, they offer less feel than the natural alternatives.

If there is a player who embodies the mechanical style of polyester tennis, it is the recent Australian Open champion Jannik Sinner, who won in Rotterdam on Sunday to go 12 from 12 in matches this year. The owner of a punishing double-hander, Sinner is technically sound and relentlessly powerful, but has so little touch that he almost could be playing in oven-gloves. For better or worse, this is the modern way.

The near-extinction of the one-handed backhand represents a grim scenario. While Sinner’s physical explosivity makes him an entertaining watch, no spectator wants uniformity. A day on Wimbledon’s Centre Court could turn into sport’s answer to Attack Of The Clones.

Barring the rise of a dominant one-hander to emulate Federer’s feats, it seems unlikely this narrative will shift back in the opposite direction. And one reason is the increasing emphasis placed on success at a young age.

Promising players are being picked up by management agencies and national federations when they are in their early teens or even younger. Yet it’s difficult to swing with one arm when you’re not physically developed – which is why Pete Sampras didn’t make the transition until the age of 14. As a coach, you are taking a risk in teaching this increasingly old-fashioned shot, in the hope that it will come good once a player has gained strength over the next couple of years.

The sight of a photogenic one-hander in full flow is one of tennis’s great pleasures. The beguiling beauty of Richard Gasquet’s single-hander earned him the nickname “Le Petit Mozart” – the ultimate backhanded compliment.

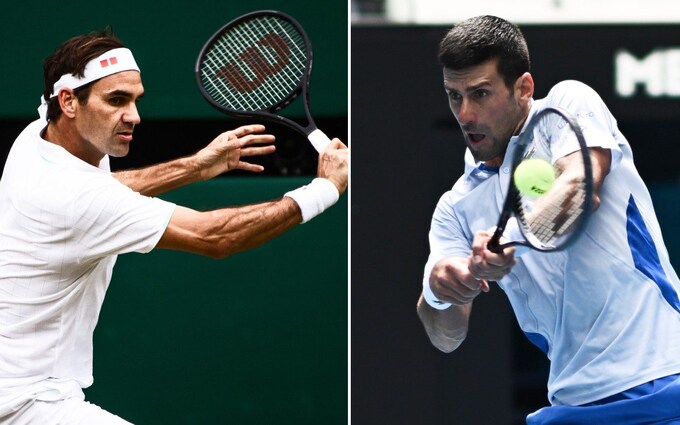

In recent years, two of the most spectacular performances on the ATP Tour have seen one-handed maestros take down Novak Djokovic. Think Stan Wawrinka at the 2015 French Open final, and Dominic Thiem at the ATP Finals in 2020. On both occasions, Djokovic saw backhand winners fly past him from all directions.

Overall, though, Djokovic has won many more of these battles than he has lost. The owner of the most reliable two-hander in history, he is also building an unanswerable case to be considered the greatest player overall. Which is just one more reason why modern coaches feel that the one-handed ship has sailed.

“In its very best form, the one-hander gives you more spin and more power than a two-hander,” said Betton. “But to be able to hit like that you need a big upper body like a Wawrinka or a Thiem. Those guys can attack off the backhand side, and hit winners from behind the baseline. They can use their strength to absorb the pace of the modern game, and to create their own. In general, though, it’s more common to see one-handers getting bullied.

“I’d like to say that there’s a new generation of one-handers on the rise at Challenger level [the next tier down from the ATP Tour] but I’m just not seeing it. The only exception is this 6ft 8in French kid called Giovanni Mpetshi Perricard, who has that same powerful physique I mentioned before. Otherwise, the one-hander is swimming against the tide.”